Finale: An overview

Over the

past 12 weeks we have examined the critical role politics plays in developing

and managing shared water resources mainly on the Nile. The interaction between

governments, communities and private enterprise have been at the forefront of

this research- with the end goal of highlighting the importance of a

collaborative discourse between all stakeholders, establishing a common goal for

the long term sustainable future of water resources in East Africa.

“African water management is also, by definition, transboundary water management” (Kimenyi and Mbaku, 2015 p1)

“African water management is also, by definition, transboundary water management” (Kimenyi and Mbaku, 2015 p1)

|

| The Nile River (Waddington, 2014) |

From a

development perspective, population change and demographic transitions have

been key in the discourse surrounding contemporary water management frameworks.

In 1990, the Nile basin population was 160 million, today this figure has

increased by 40% to 224 million people (almost ¼ of Africas population) (Appelgran et.al, 2000). Nile

Basin Initiative’s (2012)

report on the state of the Nile River Basin highlights population growth as ‘a

two-sided development issue’. A large, and growing population on the one hand

results in improved economic growth and greater human activity resulting in the

increasing capacity for improved living standards and wealth creation. However;

on the other hand, population growth in the context of a transboundary water

source results in increasing demand for water resources, and consequently

increased inter-regional competition and conflict- which often results in the

unsustainable and unregulated development of shared water resources. Thus, the

debate over the last century has involved the need for a new, basin wide framework

emphasising a cooperative approach to water management to keep up with changing

demographic trends.

One of the main challenges

facing successful water management embodies Hardin’s (1968) theory, the tragedy of the commons. External to state

development, and private sector projects- for sustainable water management to

be successful in the long term, local communities and nations need to

understand the shared water vision. Long-term benefits need to outweigh short

term returns, and people need to be educated on the importance of integrative

management approaches.

From a hydro-political

stance, Klare’s (2001)

water war’s theory, provides a hypothetical projection of the future of water

resources “transforming peaceful

competition into violence” (Barnaby,

2009), allowing hydro-diplomacy to gain significance in the field of hydro-politics

and in water management discourse. This has been challenged in literature

(Barnaby, 2009; Pohl

and Schmeier, 2014), as cooperative frameworks have always outweighed water

conflicts in the past, and with a growing academic field in cooperative water

management, a war over water is unlikely to occur. Ultimately, good water

resource management must consider issues of population, poverty, environment as

well as consider perspectives from all stakeholders with an influence on water

distribution.

Summary and Recommendations

-

Political

and economic conditions have a more significant impact on water availability

and thus water scarcity than the prevalence of physical water resources in a

nation.

-

Power

of the commons: A theme prevalent through all blog posts on the interaction

between humans and their natural resources. Water users need to understand the

need for shared planning regarding transboundary water sources. Self-interest

isn’t sustainable for such a fragile source.

-

Water

wars: In the context of Egypt and the rest of the Nile’s riparian states, a

shared vision has been lacking historically, and increasing demand for water by

upstream states has made Egypt vulnerable to water shortages, and thus ready to

fight for the water they have majority rights over.

-

A

positive breakthrough: disregarding historical frameworks and creating

discourse for shared water resource management, and equitable distribution of

water amongst riparian states. The starting point of the (hopefully) positive

development of the Niles waters.

-

Emphasis

on long-term development

-

Historical

frameworks are outdated, and need to be revised to keep up with modern trends

in development.

-

Post-colonial

Africa remains tied to colonial activity through such frameworks, which were

developed purely out of self-interest with little regard to other riparian

states.

-

Collaboration between key stakeholders is

crucial to the sustainable future of water development. There needs a balance between

private enterprise investment and government intervention and guidance.

Ultimately, governments need to create a facilitating environment for

sustainable development, so private enterprise can work towards a more

cooperative, inclusive future.

-

IWRM

needs to transition from being a theoretical concept, to being put into action.

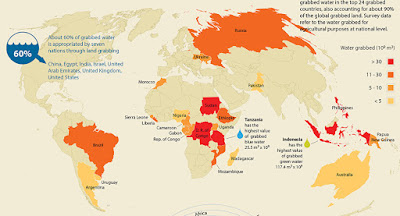

- A contemporary example of a non-collaborative approach to the

distribution of water, driven by monetary incentives for local governments ignoring

the benefits of all, in exchange for the profit of a

few (Callicott,

1991). Lack

of control over the allocation of water resources, allowing large foreign

companies to grab land for agricultural purposes. The water resources that come

with this land are taken without considering the social and environmental consequences

of local populations, whose access to land and water is often disregarded by

governments and large corporations creating a negative spiral of poverty and

hunger.

Thank you for joining me on this enlightening journey, I hope you now have a greater understanding of the nature of transboundary water resources, and the political complexities that come along with it.

Comments

Post a Comment