Integrated Water Resource Management: The case of Ethiopia

Hello everyone, welcome back! As mentioned, this post is going to look at IWRM in practice. IWRM is often used as a fuzzy term to explain ways of managing water resources as recommended by various international organisations as the best way forward in improving water security. However, often it isn’t adequately transitioned from a set of principles and policies into reality. This post is going to look specifically at the Berki watershed in Ethiopia as a case study, as this is one of the selected trial locations for the initial stages of implementing IWRM (Global Water Partnership, 2015).

Ethiopia is a country with immense water resource potential, however, due to the unequal distribution of water resources, as well as temporal factors influencing availability, around 50% of the population still don’t have sufficient access to an improved, safe water source. The region faces frequent droughts and floods, as well as an increasing population creating a higher demand for water resources, putting pressure on governments and water resource managers (Jembere, 2009). As an incentive to improve water security issues, and manage water more effectively, Ethiopia implemented a top-down approach involving changes in water governance across the country. These reforms were applied on three levels (Global Water Partnership, 2015):

1) Federal Level

Ministry of Water, Irrigation and Energy (MoWIE): the only government institution with responsibility for the overall management of water resources, this includes creating policies, legal frameworks, managing water projects, monitoring allocation etc.

2) Basin Level

River Basin Organizations (RBOs): due to Ethiopia’s decentralised government structure, this level acts as the highest decision-making body in charge of ensuring the integrated management of a single source of water. In 2015 three RBO’s were introduced on different lake basins.

3) Local Level

Currently, 9 regional states have a Regional Water Bureau (RWB) in charge of small-scale water resource management projects; this includes developing water for domestic uses (pipes, boreholes, wells), delivering water and sanitation, as well as irrigation development. Local level organisations often receive funding/support from regional (woreda) governments.

Berki Watershed

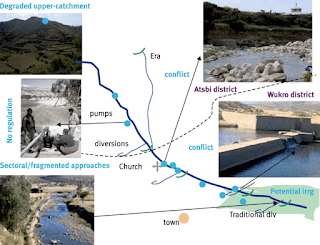

The Berki watershed is in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia, and it lies within the Tekeze river basin. The river is shared by three districts; Atsbi (upstream), Wukro and Enderta (downstream). This river was selected as part of a trial for implementing IWRM in Ethiopia and thus has received attention in the literature on water management (UNESCO, 2009; Hailu et al. 2018; Jembere, 2009).

The Berki watershed previously faced issues surrounding the equitable distribution of water sources. Due to the transboundary nature of the water source (flowing through three separate regions), there have been conflicts between riparian areas due to rising demands for water. Ultimately, government institutions and regulatory bodies on all levels had opposing interests on managing this water source- due to the lack of policy or legal framework on the river, different groups were managing the source for their own benefit, with little regards to other regions who relied on this source for survival. Wukro and Enderta regions were directly impacted by an abundance of water pumps and diversions by the Atsbi region upstream. Additionally, Atsbi region was polluting the water affecting the downstream quality (Jembere, 2009). This tragedy of the commons (Hardin, 1968) was the result of the lack of a plan, water users were exploiting the resource uncontrollably as there was little understanding of the importance of effectively managing this source.

What has been done?

To improve and equitably distribute water resources on the Berki watershed, a multi-stakeholder participatory planning approach was implemented. This involved understanding who the key stakeholders were and the needs of these groups in a variety of sectors. To do this, Ethiopia introduced a range of organisations with the intention of creating discourse among stakeholders. On a national scale, Ethiopia launched the Ethiopia Country Water Partnership in 2003, with the goal of ‘promoting and implementing IWRM’. Members of this group include government officials, local and international NGOs, donors, research institutions, women and the private sector. Every year an assembly is hosted to discuss progress, challenges and potential for improvements to the equitable and sustainable use of various water sources (Jembere, 2009). Additionally, on a basin level, the Tigray Regional Water Partnership (TWRP) was formed, comprising over 30 members representing different water stakeholders. This group creates a training and technical team for various sectors, assess the water quality and usage, as well as forms relationships and shares information on the needs of the broader population who rely on this water source. On a smaller scale, regional committees formed an alliance with governments, NGOs and local communities as an effort to balance water needs (Jembere, 2009). Each of these newly formed institutions has created an opportunity to lay a framework for integrating and coordinating activities, and have created a shared vision for the future of the Berki watershed.

For IWRM to be successful, it must be understood as a process with long-term returns. When people realise the long-term significance of sustainable management of water, real change can be made. In this specific case, local communities and water users had to be made aware of how their actions influence not only other users but their own ability to keep using this source at such a rate in the future. To drive such changes, the government’s commitment to enabling change through policy-making and legal institutions played a significant role (Jembere, 2009). Since such changes have been made, there has been a definite shift in communities’ awareness of resource ownership, and previous conflicts over water were abolished with no legal action or intervention required.

However, Hailu (et al. 2018) suggests that despite the efforts, IWRM in Ethiopia has been unsuccessful. This has been due to the lack of political commitment and the lack of appreciation for the fact that IWRM is a process based scheme, and will not have immediate advantages to water availability or quality. The inability for communities to see direct benefits or linkages to their lives is one of the critical challenges countries face in attempting to implement IWRM frameworks.

Comments

Post a Comment