History of Water Politics on the Nile: A Postcolonial View

Hello, and welcome back to my blog. This week I will be looking at the Aswan Dam, and how colonial treaties have favoured Egypt, leaving other riparian states with little say over the management of the Nile's resources.

The unreliability of the River Nile’s flow has been recorded for thousands of years. The Ancient Egyptian civilization grew up along its banks and was very aware of the reliance on the river for its survival.

The unreliability of the River Nile’s flow has been recorded for thousands of years. The Ancient Egyptian civilization grew up along its banks and was very aware of the reliance on the river for its survival.

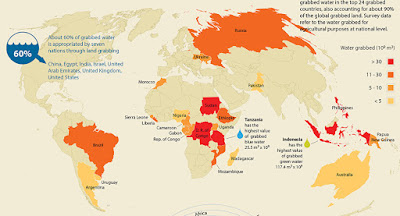

As one of the most developed and populated regions of the Nile, Egypt has historically been the major user of Nile waters which provided fertile soil for the ever-increasing land taken up for agriculture. As colonies became separate countries, populations grew along with the demand for food. The demand for water by not just Egypt, but many of the Niles’ riparian states increased and became a contentious political platform. Poor economic development in many of these states and a lack of investment in programs to increase efficiency in water allocation led to water deficits in many countries (Howell and Allan, 1994). Based on a treaty signed with Sudan in 1959 (The Nile Waters Agreement), Egypt laid claim to 2 thirds of the Niles flow and ensured its short-term supply with the building of the High Aswan Dam in the 1960’s. Despite hydrologically more sustainable plans for a water storage reservoir in the uplands of East Africa, the Egyptian leaders at the time sought to secure control of the water supply, so the dam was built near the Sudanese border, giving Egypt almost exclusive control of the Nile waters.

Built at a time when the world was less conscious of the environmental impacts of such large development projects, the designers of the Aswan Dam were aware of the important social and environmental issues surrounding any construction that would control this vital water supply. The benefits to Egypt are in no doubt. The dam generated hydropower, that by the late 1970s accounted for nearly half the electricity generated in the country. Increasing industry, land for agriculture and a much-improved standard of living for many Egyptians followed the dam’s construction (Biswas and Tortajada, 2012). Egypt was protected from the devastating impacts of the long drought of 1979-1986 and the subsequent floods of 1988 that proved so catastrophic for its upstream neighbors; Sudan and Ethiopia.

By the 1990’s, the need for some sort of sustainable system of water cooperation and regulation came to the attention of many governments and agencies around the Nile basin. The 1959 treaty giving Egypt majority rights over the water supply was no longer enough to maintain a growing population and the agriculture to feed it. Other Nile basin countries were needing more water to feed their growing populations and economies. The Nile Basin Initiative was drawn up with the hope of developing water resources in an equitable and sustainable way (Belay et al., 2009).

This brief post-colonial insight on water management on the Nile has led us to an understanding of the key concepts surrounding the formation of the Nile Basin Initiative as discussed in my previous blog post. To build on this current theme of the history of water management on the Nile.

Hi, I have enjoyed learning more about the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) and the key drivers for it in your last 3 posts. How has the Egypts control over the water in the Nile or use of the High Aswan dam been impacted by the NBI? is there literature that suggests the water availability in the other states has improved as a result of the NBI?

ReplyDeleteHi Marie, thanks for these great questions- they've got me looking more in depth on how successful/unsuccessful the NBI has really been.

DeleteThe NBI was not set up to be a solution to water management issues on the Nile, rather it was put into place as a means of creating a shared vision amongst the Niles riparian states- highlighting the need for a more cooperative, basin wide framework, regulating water in a more equitable way. Ultimately, what the NBI has done is set up appropriate programs which have focused on developing institutions, provided training and encouraged the sharing of data and information. The programs that have been developed as a result of the NBI have led to a significant increase in discussions regarding the need for a revised framework- and Egypt have begun to understand the needs of other riparian states, despite their position as having the majority of the Niles flow.

However, there appears to be limited literature discussing actual impacts of the NBI on Egypt’s water use, other than the fact that upstream development projects (like the GERD) may reduce the quantity of water reaching Egypt and other downstream nations. This lack of research may be due to the fact that the NBI hasn’t gone far enough. In 2010, 5 upstream countries signed a Cooperative Framework Agreement to seek more water from the Nile, an agreement which was refused by Egypt and Sudan- suggesting that although Egypt are open to dialogue surrounding cooperative development of the Nile, they don’t appear to be open to sacrificing any of their water resources, as it is so crucial to the wellbeing of the nation.

Hi Georgia,

ReplyDeletethis was a very interesting post about the historical background of the use of water in the region of Egypt. It helped me to understand why and how water was/is allocated, distributed and managed in the Nile basin, especially regarding to the former colonialist treaties which are still active, despite the independences! I really liked and particularly found interesting that you mentioned the new issues such as the higher demand of water for domestic, agricultural and industrial uses. I also liked reading it, because i could link it to what we learned in class!

(Sorry, I had issues uploading the comment before.)

Best, Fiona