Water Grabbing: A transboundary issue?

Water Grabbing

“Water

grabbing is the process in which powerful players are able to take control of,

or reallocate for their own benefit, water resources used by local communities

or which feed aquatic ecosystems on which their livelihoods are based” (Franco

et al. 2013a p1653-54). The need

for land and the water sources that come with the land has increased

dramatically as the human population has grown along with the increased demand

for food. The process of land grabbing has been happening for centuries, and is

a global phenomenon, though much attention has been paid to land, and the

associated water grabbing in Africa (Rulli

et.al., 2012).

|

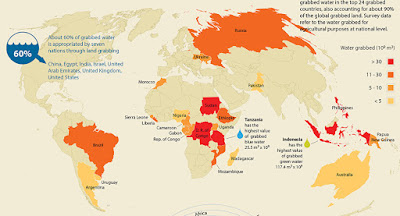

| Grabbed water in top 24 most grabbed countries (Guerrilla, 2017) |

In many

countries, the right to the use of water has often been organised at a local

level, with informal arrangements between smallholders. These local

arrangements are often disregarded as governments, and big corporations seek to

formalise the rights to water use. Many of the more recent initiatives and

regulations focus on the control of land appropriation, leaving the control of

water sources complex, unclear and open to abuse. It is challenging to devise

adequate regulations regarding the control of water resources as its

availability is so variable, being dependent on seasons, temperature and

climate change (Rulli, et.al., 2012). In the case of rivers that flow across

nation’s borders, the source of the water may be far removed from regions where

it is used, and the effects of diverting or polluting a water supply may be

felt long distances from the source of disruption.

In recent

years, millions of acres of land across Africa has been grabbed, often by

private investors and corporations for large-scale agriculture. The demand for

food and biofuels have increased, and often wealthier nations have resorted to

grabbing cheap land and the necessary water supply, in more impoverished areas

of the world. The acquisition of land is usually done legally through local

government leasing incentives; however, the control of water needed for

irrigation is less regulated and often ignores the social, economic and

environmental implications for the local population.

Tana River Delta

The Tana

River Delta is one of the most important wetlands in Africa and supports a

diverse range of wildlife, along with a population dependent on the biannual

flooding to provide grazing for cattle, fertile farmlands and fishing areas.

The Kenyan government had declared the delta land as underutilised with

potential for development. Plans were drawn up with private investors and

foreign companies for large-scale production of sugar cane and Jatropha curcas

– a plant used in the production of biofuel (Duvail,

2012). Not only

would the land be grabbed from local populations, but also the river water.

Historically, the local people had existed with informal rights of access to

water that were sustainable and beneficial to all. Minimal regard had been

given to the environmental and social implications, so environmental

organisations, NGOs and local communities began a campaign to halt the development

of the Delta. In 2012, the Tana River Delta was designated a Ramsar site.

Ramsar is an international convention for the protection of important wetlands

(Franco

et al., 2013b).

Other

regions of Eastern Africa such as areas neighbouring the River Nile have been

subject to large-scale land and water grabbing. The River Nile is a lifeline

for neighbouring states such as Ethiopia, Southern Sudan, Sudan and Tanzania

and large irrigation projects continue to be the cause of much geopolitical

discord. Historically, much of the Nile water was designated for Egypt’s use as

discussed in my previous posts. However, after the building of the Aswan Dam in

the 1960s to regulate the rivers flow in Egypt and aid in large-scale

irrigation of agricultural land, the flow of nutrients and minerals which would

normally fertilise the land for local farmers downstream was reduced. Ethiopia, South Sudan and Sudan, along with

Egypt have become targets for foreign-owned agricultural projects. Land is

leased by the governments, but it is the water needed for irrigation that is

more valuable and the grabbing of which tends to ignore the historical rights

of access by the local populations. The cheap land available for lease by large

businesses and the lack of governance over water supply has enabled water to be

diverted from its traditional uses.

The growing

of water demanding crops such as palm oil and sugar cane, which are often

exported has resulted in local subsistence farmers losing access to both land

and water, leaving the local populations dependent on international food aid.

Years of civil war in Sudan for example, along with unstable leadership has

resulted in a lack of organisation and legal controls in the allocation of

water resources. Powerless against big corporations local people are left with

high levels of malnourishment and poverty. It is difficult to see how the Nile

River can sustain such large-scale agriculture in the future without

detrimental environmental and social consequences (Grain,

2012).

The

Ethiopian government backed the construction of the Gibe III dam on the Omo

River (completed in 2015), to provide electricity and aid in irrigation of

large tracts of land leased to foreign agribusinesses, mainly producing sugar

cane. The removal of much of the water upriver for irrigation has led to

diminished supply and quality of water to the downstream regions occupied by

indigenous tribal communities in Southern Ethiopia and Northern Kenya. The

resulting poverty and hunger amongst these communities have caused local

unrest, but little concern from international businesses benefitting from the

easy grabbing of water resources for their own benefit (National Geographic, 2015).

It is

becoming apparent that there is not enough water available in Africa’s rivers

and water tables to sustain all the major industrial and agricultural projects

ongoing or planned. The depletion and degradation of water sources in the quest

for food security by wealthier nations will continue to result in poverty and

hunger in Africa where indigenous people gain little or no benefit from these

projects.

Comments

Post a Comment